alt

Medicine Wheel, Bozeman Trail Subjects of Talks

The Medicine Wheel

David Mckee, President of the Fort Phil Kearny/Bozeman Trail Association, and Donovin Sprague member of the Minnicoujou Lakota, shared the stage and talked to a large crowd on Thursday night at the Old Kearny Hall in Story. Around 50 people attended the program.

McKee, who served as the Bighorn National Forest Liaison to the National Park Service and American Indian representatives in completion of the nomination for the Medicine Wheel/Medicine Mountain National Historic Landmark, spoke on the Medicine Wheel.

He said that in 1970 The Medicine Wheel was designated a National Historic Landmark due to its unique scientific research values. In 2011, the boundaries were enlarged from 110 to 4,080 acres in response to ethnographic information regarding Native American traditional cultural of use of the Medicine Wheel and the surrounding Medicine Mountain area.

Although around 140 medicine wheels have been found in Montana, South Dakota, Wyoming and the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, the Bighorn Medicine Wheel is unique among the Medicine Wheels. It is the best-known, one of the largest and the best preserved. It was the first medicine wheel to be studied by the professional scientific community, and the first to be mentioned in popular literature.

As early as 1895 Paul Franche wrote an article about the Wheel for Forest and Stream Magazine, and in 1922 George Bird Grinnell, the famous anthropologist, visited the Medicine Wheel and published an article “The Medicine Wheel” in the American Anthropologist.

No one knows exactly how old the Big Horn Mountains Medicine Wheel is. Most archaeologists believe that the Medicine Wheel was constructed over several hundred years.

“There have been depositions in the soil suggesting it was built in phases,” McKee said.

“There has been carbon dating done on sites near the Medicine Wheel that give us a date of 6720 BC.” McKee said. “But no one knows exactly who build it.”

Preserving the Medicine Wheel is a challenge. McKee said that there is a balance to maintain, between the public, and visitors to the wheel, the multi-use policy of the Big Horn National Forest, and the Native American Tribes who hold the area sacred.

To help preserve the Wheel, in 1925 a stone fence was built around it by the Forest Service. In the 1970s, due to increased ceremonial activity, a post and rope fence was constructed around the wheel.

In 1883 the Code of Indian Offenses outlawed traditional ceremonies. Then, in 1978, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, (AIRFA) was enacted to return basic civil liberties to Native Americans, allowing them to again practice traditional ceremonies, including those on and around Medicine Mountain.

Today, after many meetings and much compromise, the Wheel is accessible for tourists via a mile and half hike up the mountain. There is a small interpretive site and a parking lot at the bottom of the road, and those who are physically challenged can obtain permission to drive to the Wheel. The Wheel is open for Native American Ceremonies, and some are private so guests are ask to wait until the private ceremony concludes.

After a short break, Donovin Sprague (Hump) spoke about his family and the part they played in the history of this area. Native American history is recorded on the ‘Winter Count’ buckskins, and passed down by oral traditions.

Sprague was born and raised on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, and is a member of the Minnicoujou Lakota and his family includes Crazy Horse and several others named Hump.

He is the author of ten books, a historian, and currently teachers history, political science, including Wyoming Tribal History and American Indian History, among other courses at Sheridan College. He also serves on the Fort Phil Kearny/Bozeman Trail Association Advisory Board.

Sprague’s family were involved in many battles against the US Army. After the Sand Creek Massacre in 1854, the Cheyenne bought the war pipe to the Lakota. By 1857, the tribes saw a lot of destruction to the lands and the buffalo herds by the white men and gold seekers. That year there was a large gathering of tribes at the base of Bear Butte near Sundance to discuss the encroachment of the white men into their country.

In 1864 in Julesburg Colorado the tribes practiced a lot of harassment of travel on the southern trails.

“The Bozeman Trail wasn’t built by the gold seekers,” Sprague said. “It was improved by them, but it was actually an old Native American trail.”

“The US Government established three forts, Reno, (near Kaycee), Fort Phil Kearny and C.F. Smith in Montana. They put those forts in the middle of a hornet’s nest,” Sprague said.

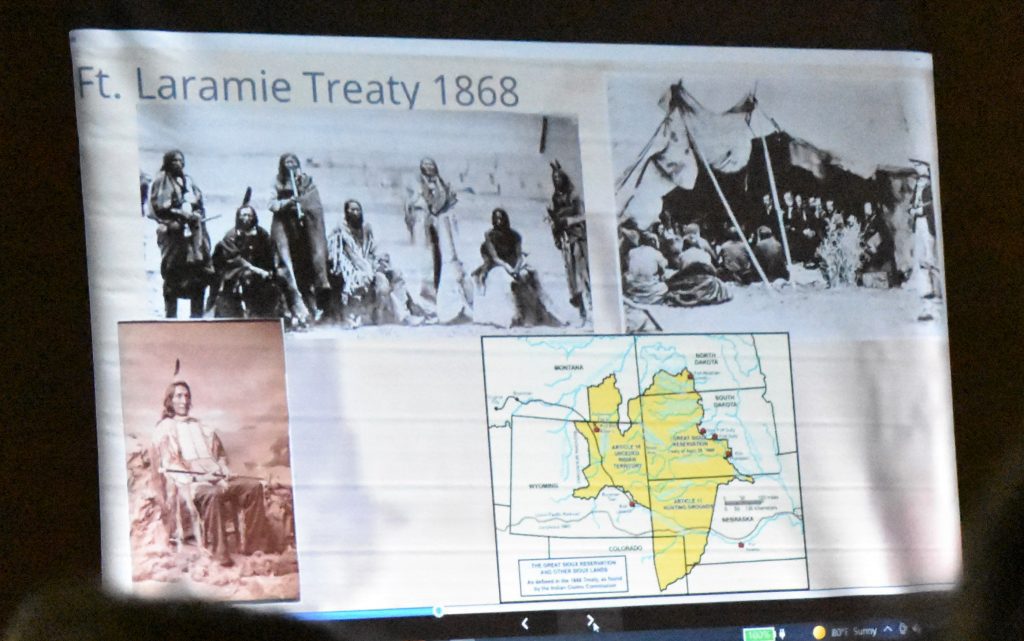

Sprague told the crowd that at the Treaty of 1868, the tribe was given a large expanse of land.

The chiefs who signed the treaty were also given hats, gifts, trinkets.

But, more and more white people came into the Lakota country, and when gold was discovered in the Black Hills in 1874, the treaty was completely violated.

There were several engagements between the army and the tribes, many near Story and Fort Phil Kearny; the Wagon Box Fight, the Fetterman Fight, the Connor Fight, and the Battle of the Rosebud.

“The Little Big Horn was the last major battle,” Sprague said. “My great-grandfather Hump Two fought at Little Big Horn. After that, most of the Indians eventually surrendered, except for Sitting Bull and Hump, my ancestor, who went to Canada.”

Sitting Bull remained there until 1881, at which time he and most of his band returned to US territory and surrendered to US forces. Sitting Bull was later shot and killed at the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota.

Sprague ended his talk with a haunting flute solo.

Eliot Kalman

August 16, 2021 at 6:01 am

It has been many years since I last visited The Medicine Wheel, so I’m not certain how the possible rearrangement of the stones by individuals with righteous or otherwise motivation might have happened, but assuming it hasn’t changed that much, the choice of photographs to accompany this article does a disservice to the reader. Like, for example, the Serpent Mound in Ohio, one really doesn’t understand the site without perspective from above. Without seeing it from on high, the beautiful Serpent Mound looks like a meandering grassy knoll, and the beautiful Medicine Wheel just looks like a formless assemblage of rocks. If one spends a sufficient amount of time in either place, one can get some idea of what the originators of the Serpent Mound and the Medicine Wheel were conveying, but a photo or two of either, except from above, just won’t do it

Suzanne Vesely

August 16, 2021 at 1:43 pm

So glad that this site is being cared for. I recall when I was a small girl going there and seeing huge masses of antlers on each cairn–and no barriers at that time. Too bad the barriers are necessary–but we still have the Wheel, and that is what matters. I try to go there every summer, although I missed the trip to Wyoming in 2000.

Teresa Teddy Araas

August 16, 2021 at 2:32 pm

Thank you for posting this important information from excellent speakers ~ I too grew up loving treks to the Medicine Wheel, and continue to do a pilgrimage yearly in summer, either alone or with members of my Santosha Yoga Center community… TYQ (Teddy)