News

Arapaho Language Subject of Talk

On June 16th the FPK/BTA (Fort Phil Kearny/Bozeman Trail Association) presented an Introduction to the Arapaho Language with Professor Andrew Cowell, University of Colorado.

Cowell is the chair of the University of Colorado Department of Linguistics. One of his main research interests is the indigenous languages of the Western U.S., and he directs the Center for the Study of Indigenous Languages of the West (CSILW). He has published extensively on Arapaho, and also works on Gros Ventre, Arapaho, and Miwok.

Wayne C’Hair, member of the Northern Arapaho Language and Culture Commission, was unable to come to the program, but told the Arapaho story about the origin of Devils Tower and the Big Dipper constellation via a previously recorded video.

Cowell spoke about the Arapaho and Cheyenne languages, which are considered an Algonquian languages, related to the Blackfoot, Cree, Ojibwe, Delaware, and several others.

He also mentioned that the Shoshone and Ute language was actually an a branch of the large Uto-Aztecan language family, and the Shoshone and Ute are actually related to the Aztecs. There is a lot of research going on to understand how the native tribes ended up where they are. There is a big controversy about the Aztec’s, whether the Utes came north or the Aztecs went south.

He said that as opposed to Europe, where one language family predominates, in North American there were dozens of different language families and more language diversity than in all of Europe.

He said that Lakota language is a completely different language family, unrelated to the other two. He talked about how to pronounce some of the Arapaho words, and how difficult it is to learn the language, as it is so different from English. In answer to a question about Sacajawea and how she was able to talk to Lewis and Clark on the expedition,

“You can understand how there might be some confusion there.”

He said that if one don’t grow up learning a language like this, it is very hard to learn it. It is tough to translate from Arapaho to English as many times the Arapaho language does not actually have a word for something as the English language does.

He wanted to emphasize that many Native American languages are disappearing.

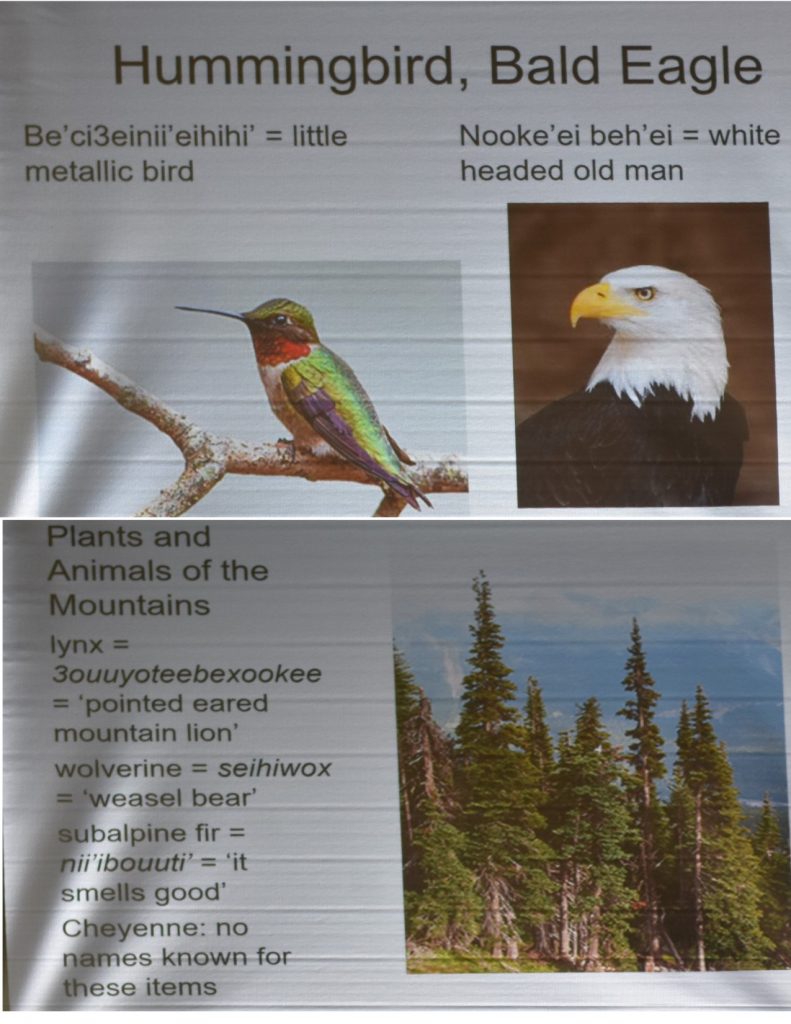

Cowell talked about the connection between language and culture. “I think that language and culture are infinitely connected, and people are interested in how language shows culture.” Many people think that Arapaho was mainly a plains tribe, but they also had names for several mountains and other areas in Colorado.

Cowell said, “This proves the Arapaho territory was much more extensive than just the plains. They had to have spent a lot of time in the mountains to have names for these areas that you can’t see from the plains. Linguistic research helps to demonstrate social and cultural history and geography and landscape.”

As well as several mountain names, they also have a name for a lynx and a wolverine, so the Arapaho had to have interactions with these animals. The Cheyenne was not a mountain tribe, and they had no word for either of them.

He added that many rivers still bear the English translation of the Native American names, such as Tongue River and Goose Creek. Rivers were travel corridors and everyone used them so the names were shared with other tribes. Towns would be named after the rivers they were on. Summits were used as guides, and they might name them, but most tribes did not name the entire mountain ranges.

He said that a fort was a ‘soldiers’ house’, and Fort Fetterman was named ‘Stingy House,” as the soldiers there had a bad reputation among the Indians for not having many trade goods.

He said that these languages can be eloquent and sophisticated and were not in any way primitive. He recited an Arapaho poem and mentioned that in Arapaho, four is a sacred number, and everything is done in fours. This is another reason that the language is more than language but is tied into culture and the prayer reflects the Arapaho worldview. As one line of the poem says, ‘(We ask for good) thoughts, a (good) heart, love and a joyful life.’

That is one reason that the tribal elders don’t want the language to be lost.