News

Fort Reno: Guarding the Bozeman Trail

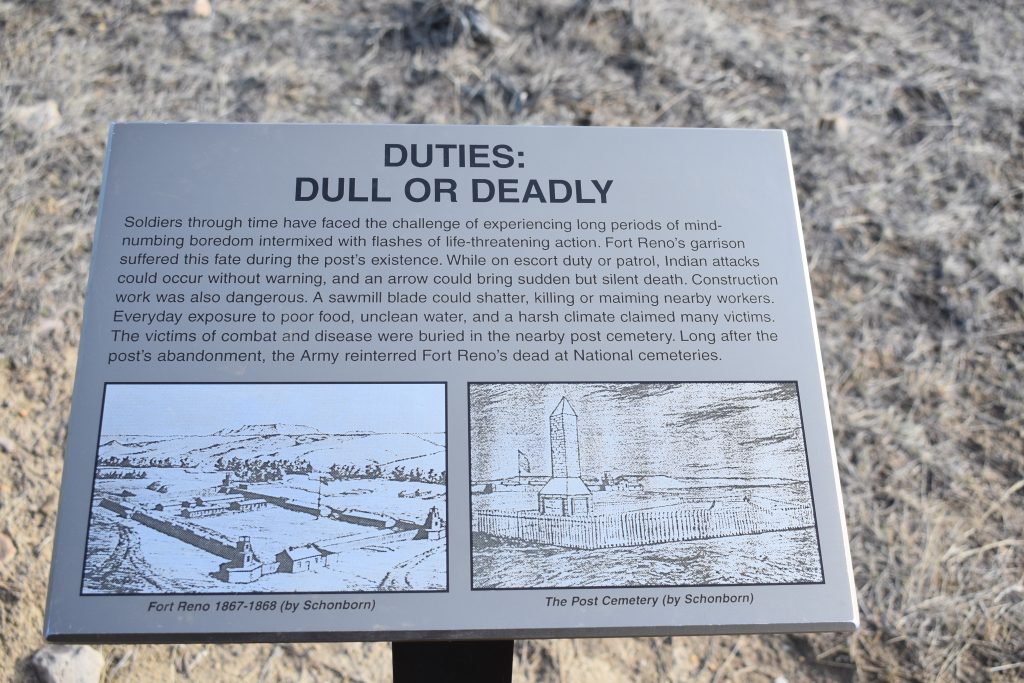

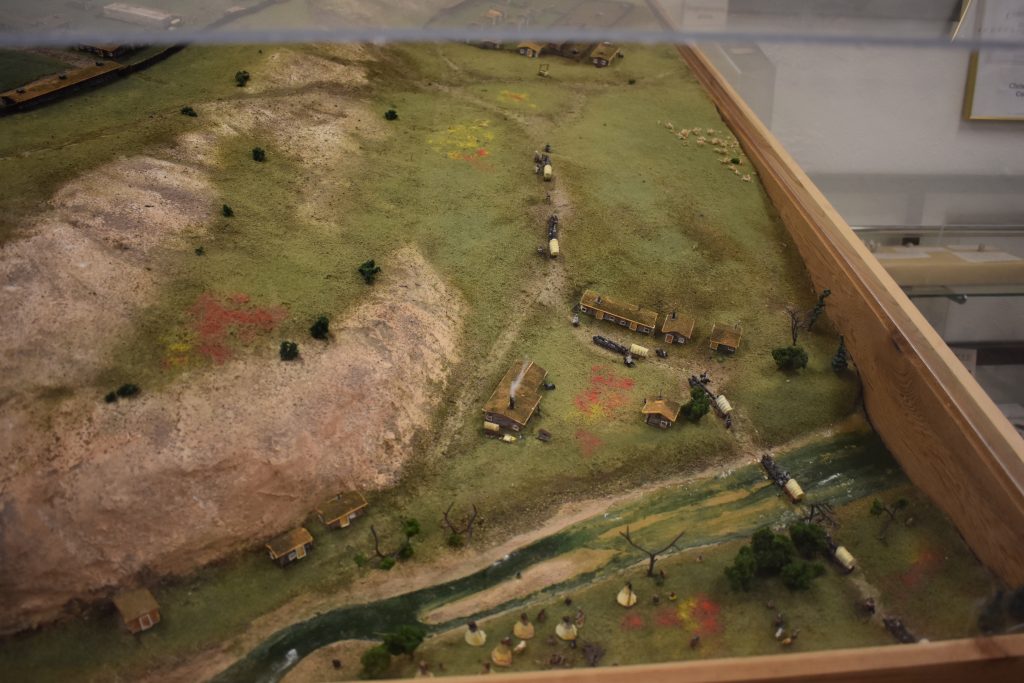

A composite photo showing a re-creation of Fort Reno on the site. Diorama at the Hoofprints of the Past Museum in Kaycee.

In 1865, General Patrick Conner commanded the Powder River Expedition, with the intent of finding a place to construct a fort on the Powder River in Dakota Territory to protect gold miners on the Bozeman Trail. Along with Colonel James Kidd and around 600 men, the expedition left Fort Laramie on August 1.

On August 15, 1865, a site was selected for the fort, on a bluff above the Powder River. The Bozeman Trail, an old Indian and trapper trail that was used by gold miners going to the Montana gold fields, crossed the Powder River below the site of the new fort, which offered the emigrants protection along the trail.

Construction began immediately. The new post was at first christened Fort Connor. in honor of their commander. Fort Connor became the jumping-off point for the soldiers that fought at the Battle of the Tongue River, near present-day Dayton, Wyoming, on August 29, 1865.

At first, the fort was just a tent encampment, but soon a sawmill was built, and more buildings; barracks, warehouses and work buildings were constructed. The buildings had sod-covered roofs and dirt floors. Leading the soldiers to liken their existence to that of a prairie dog.

Later a log stockade was built, complete with log bastions on the northwest and southwest corners. The garrison ranged from 125 to around 300 soldiers during the three years it was in use.

In November 1865, the fort’s name was changed to Fort Reno, in honor of Major General Jesse Lee Reno a civil war commander. The winter of 1865-’66 was brutal, and the garrison suffered 33 casualties, including the commander, Captain George W. Williford, who died of illness in April of 1866.

The tall flag pole with the American flag flying proudly in the Wyoming breeze must have been a welcome sight to the travelers in the covered wagons along the Bozeman. It spoke of protection, a rest stop, and a place to get news about the trail ahead.

Protection was necessary. Many of the Indian tribes resented the white men with their covered wagons moving across their hunting grounds. There were attacks on the emigrant trains, and cattle and horses were stolen by the Native Americans. Trying to bring some kind of peace to the plains was an on going problem for the army.

In the Cheyenne Leader, September, 1867 there is a report about the peace talks between the army and Indian tribes. Movements of the Peace Commission: The peace commission has decided to go to the North Platte, and thence to Julesburg, and perhaps to Cheyenne. After seeing all the Indians that can be induced to make their appearance at those places or intermediate points, they will go to Fort Larnard, Colorado, and not go to Laramie until the first of November. This change in the programme, (sic) was necessitated by the news from Laramie. The runners sent across the country from Fort Thompson, and others who have come in report that the hostile bands decline to appear until the soldiers have evacuated Fort Reno, Fort Smith and Fort Phil Kearney, the forts in the Powder River Country. They also say that they will not come in separately, but jointly, and that they shall hold a council on their own before doing anything.

This somewhat complicates the business, and some begin to assert that the commission is a failure. I do not think that statement is as yet correct, nor that the ultimatum of the Indians, one which they put forward to show their continued desire for war. I

It is probable that at Julesburg the chiefs of the bands that have been infesting the lines west of there may be met and brought to terms. The commission is in session to-day and will leave here to-morrow, and meet Spotted Tail at North Platte, hence proceed to Fort Larned, Colorado, then Julesburg and Denver. The government commissioners are expected reach here next week for inspection of additional sections of the Union Pacific Railroad, which will be four hundred and sixty miles from Omaha. – Chicago Tribune 18th.

Fort Reno was only an active fort for three years, and in 1868, as a part of the Fort Laramie Treaty, and to bring an end to Red Cloud’s War, the land in the Power River County was ceded to the Lakota Sioux.

In the Cheyenne Leader, June 5, 1868, The SpecialOrder for the Abandonment of the Upper Posts has been made public, and the method of removing the supplies and forces are explained as follows: Headquarters Department of the Platte, Omaha, Neb., May10,1868. Special Order, No. 80.

1. Under orders from the General in Chief, the military posts of C.F. Smith, Phil Kearney and Reno, on what is known as the Powder River route, will be abandoned. The public property of Fort C.F. Smith will be sold at public auction, and that at Forts Phil Kearney and Reno— commencing and finishing first with the former— will be transferred to such of the lower posts as the Chief Quartermaster of the Department shall direct.

2. Upon the sale of the property at Fort C. F. Smith, the troops there will be transferred to Fort Phil Kearney. When the property is removed from the latter post, the troops will go to Fort Reno, and remain until the stores are removed, when the whole command will proceed to a convenient camp on the railroad, near Fort D.A. Russell, and await further orders.

3. As soon as transportation arrives at Fort Phil Kearney, the commanding officer will send Major Smith and two companies of the 27th Infantry to relieve the18th Infantry at Fort Reno.

4. On being relieved at Fort Reno by the 27th Infantry, Major Van Voast, 18th Infantry, with the portion of his regiment at that post, will proceed direct to Fort Russell, and report for further orders.

5. Brevet Major E. B. Grimes, Assistant Quartermaster, will proceed to Fort Phil Kearney, and in conjunction with Brevet Major General John E. Smith, Colonel United States Infantry, will carefully inspect all public property at those posts, and condemn all not worth transportation. Major Grimes is further charged, under special instructions from the Chief Quartermaster of the Department, with a supervision of the packing, loading and transporting of all the stores at the afore said posts. By order of Brevet Maj. Gen. Augur.

Later, a fire swept through the fort, destroying most of the wood buildings.

During the Sioux War of 1876, General George Crook and his men returned to Fort Reno in March, but all that was left were a few adobe walls and debris. Nevertheless, Crook set up a supply base there for 15 days, leaving the expedition’s supply wagons and an infantry regiment.

In the Cheyenne Weekly Leader, March 25, 1876 has a report about Crook’s return. News from Northern Wyoming. From our Special Cor. at Fort Reno, Fort Reno, on Powder River Wyoming.

March 13, 1870, to the Editor of The Leader: I send you the following notes which, if not very important, may interest your readers. We left Fort Fetterman on the 1st, with forty day supplies, ten companies of Cavalry and two of Infantry, seventy-five mule teams and two hundred pack mules.

Col. Stanton commands the scouting party, twenty-five in number, as fine a body of frontiersmen as can be collected in the country. On the night of the 2nd our beef herd was stampeded by Indians. Fifty-two head were driven off, but recovered by the soldiers; in the attack one herder was slightly wounded. On the evening of the 5th we had another attack from our red friends; we were encamped on the Powder River, opposite old Fort Reno.

The casualties were: one soldier wounded in the cheek. Tuesday, March 7th. — Gen. Crook left us at Crazy Woman Fork, accompanied by the cavalry, the scouts and the “packs.” We are now encamped upon the ground where once stood Fort Reno, awaiting the return of Gen. Crook and command. We have not heard from the General since he left. Everything is quiet here, owing to the very cold weather, but we expect trouble at any moment and we are prepared for it. Two companies of soldiers and seventy-five teamsters are well armed, and would be able to give the Sioux a lively deal. I expect to return to Fetterman as soon as Gen. Crook returns to camp; then send you more news. M. M.

A year later, in the Laramie Daily Sentinel, October 1877, a gold seeker travels the Bozeman passed Fort Reno looking for gold. No Gold in the Big Horn Country. [From the Greeley Sun] K.M. Boynton arrived in town on Tuesday, after a long absence in the Black Hills and Big Horn country. We published several months ago a letter from him, in which he gave his opinion of the mining prospect in the Black Hills and stated that he was about to start for the Big Horn country. With a party of thirty-five he left Deadwood on the 16 of June, and went in a southwest direction to old Fort Reno, crossing the Belle Fourche on the way.

From Fort Reno they followed the old military road along the eastern base of the Big Horn mountains to Fort C. F. Smith, situated at the mouth of Big Horn Canon (sic). On their way they crossed the stream known as Crazy Woman’s Fork, Clear Fork. Piney, Goose Creek, Little Big Horn, and Big Horn. They did not find a single color of gold in any of the streams heading in the Big Horn Mountains.

Game was abundant. Elk, deer, antelope, buffaloes, and bear were in sight frequently. The country east and north of the Big Horn Mountains was a fine stock country, if the winters are not too severe. Mr. Boynton thinks the grass was the best he has seen. The rivers bounded with fish. No whites have settled in the country. During all their journey between Fort Reno and Camp Brown, they saw not a single white habitation, outside of military encampments.

Today, there is nothing left of Old Fort Reno. In 1914, a monument marking the location of the fort was set up by the State of Wyoming and the citizens of Johnson County. It lies between Kaycee and Sussex, and there are interpretive signs set up just off the road giving a brief history of the fort.

In the Hoofprints of the Past Museum in Kaycee, there is a diorama of how the fort looked in the 1860s. It has been listed on the National Registry of Historic Places, a reminder of what it took to tame the wild and woolly Wyoming plains.