News

145 Years Ago Custer Met His Fate

A cut out of Custer at the Little Big Horn Battlefield Museum at the Visitor’s Center at the Battlefield

On June 25, 1876, Lt Col. (General) George Armstrong Custer, met the Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes in his fatal battle on the Little Big Horn River in what is now Montana. As there were no survivors of Custer’s troop on Last Stand Hill that could tell the tale, the battle is still shrouded in many mysteries. Even 145 years later, the Battle of the Little Bighorn captures our imagination, and new information keeps coming to light about the famous battle.

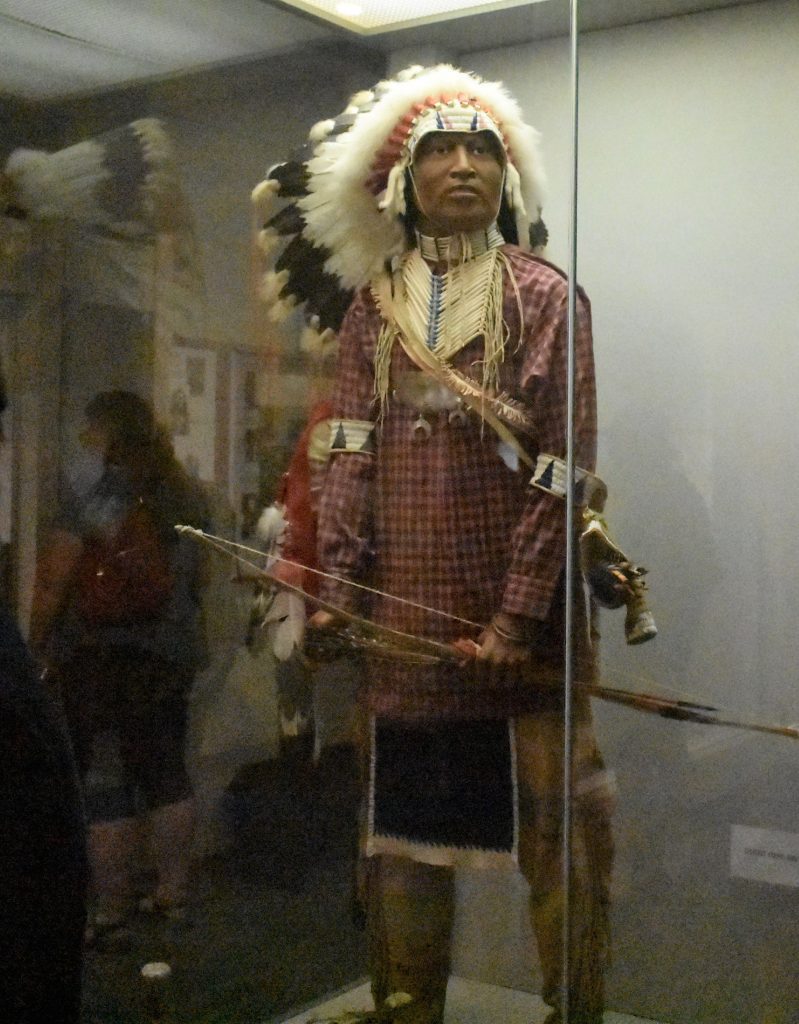

The Battle of the Little Big Horn was the last overwhelming victory for Native American warriors, mostly due to the Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull. When Red Cloud and Spotted Tail signed the peace treaty at Fort Laramie on July 2, 1868, Sitting Bull stubbornly refused to meet with the US Government officials. He told the Jesuit missionary, Pierre Jean DeSmet, who spoke to him on behalf of the government: “I wish all to know that I do not propose to sell any part of my country.”

But, the US government was under pressure from gold seekers and settlers to open the Black Hills Country. Failing in an attempt to purchase the land, President Grant ordered all Sioux bands to move to the Great Sioux Reservation in what is now South Dakota. Grant knew that many of the Sioux would not comply, thereby allowing the military to pursue the tribes as hostiles.

As an Oglala chief, Low Dog, stated after the Reynolds attack at the Powder River Indian Camp in March 1876, “When it begin….we would have to yield of fight….the white man has no right to say where I shall go or what I shall do.” (1876 Facts about Custer and the Battle of the Little Big Horn Jerry L. Russell 1999 Da Capo Press.)

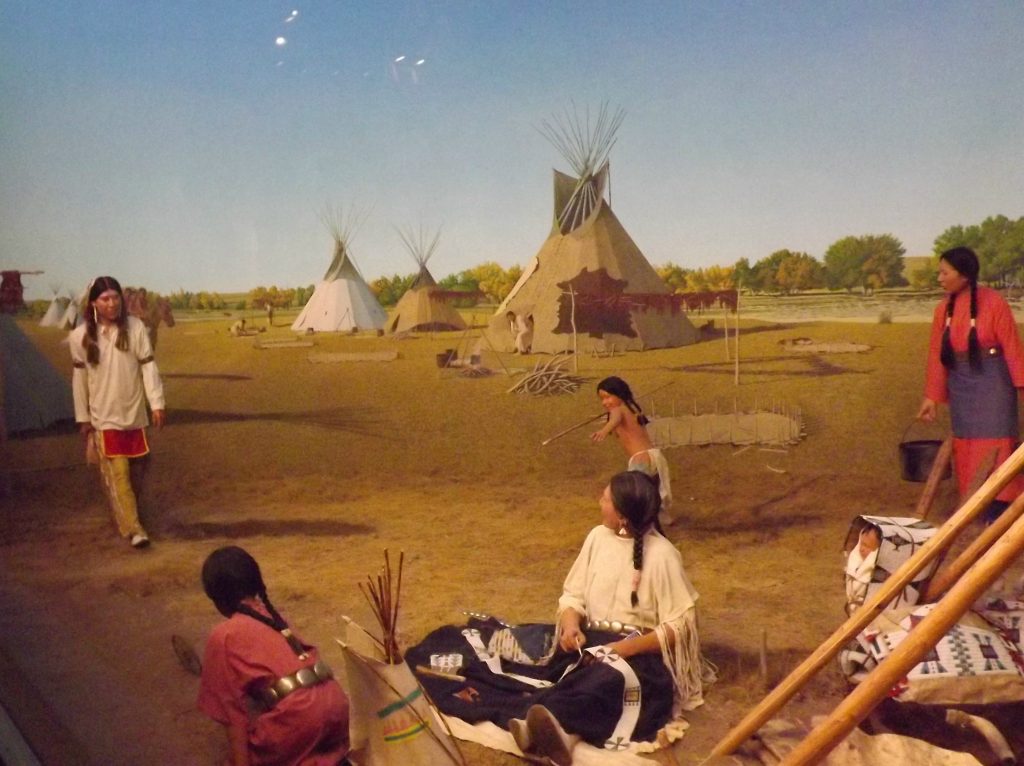

This was the reasoning of many of the Native Americas. They wanted to roam across their hunting grounds and living the life they had always lived. The coming of settlers made this impossible. With the settlers came wagon trains and freighter and steam boats.

Although the country around the Little Big Horn River is pretty dry and the creeks are small, it isn’t far from the Powder River, which flows into the Missouri. During the 1860s and 1870s, riverboats were common on the Missouri River, the Yellowstone and the Powder River.

Even before the historic battle against Custer, Sitting Bull was actively attacking the white men that invaded his lands. In the Cheyenne, Wyoming, Weekly leader on July 22, 1876. “…(Sitting Bull) made war on the steamboats and commerce of the Missouri, massacring several small boat-loads of returning miners, and capturing large quantities of gold dust, which he traded for arms with the northern half-breeds.” The army needed support from steamboats, so the constant harassment made it difficult to get supplies back and forth.

In an article in the Cheyenne Weekly Leader, May 27, 1876 “The steamer Josephine has landed her first cargo of expedition supplies, and three companies of infantry at the mouth of Glendive Creek, on the Yellowstone, which will be General Terry’s base of supplies up the Yellowstone. Fort Buford dispatches state that three companies of infantry and two boat loads of provisions have arrived at the mouth of Glendive creek, where Terry has established a supply station for his own and Gibbons’ commands. Custer leads Terry’s advance with two companies of cavalry. No engagement has as yet taken place, but signal fires of the Indians are seen every night. The Indians are thought to number about 8,000 warriors.”

Later in that year, the US 7th Cavalry, lead by the charismatic George Armstrong Custer, (last in his class at West Point, in 1861, but given the commission as General during the Civil War) was actually a lieutenant colonel at the Little Big Horn battle. He led a force of 700 men into the Little Big Horn River Valley on June 25, 1876 pursuing the Sioux.

What Custer did not realize until it was too late, was the fact that the Sioux had been joined by a large contingent of Cheyenne, and Arapaho that disliked the idea of being forced off their lands. Sitting Bull was not fighting in the battle, the fighting was left to Crazy Horse and Chief Gall.

In the article June 22 article, “…Sitting Bull defies the government, and hopes that he can get the Sioux Nation to join him. If they will only do this he promises to drive the whites back into the sea, out of which they came. He utterly disbelieves the report of Red Cloud and others who have visited the East as to the numbers of the whites they saw. He says their eyes were drizzled by bad medicine (magic). Ordinarily his followers comprise not more than 200 or 300 lodges; but there is no doubt that his numbers are now swelling. The Northern Cheyennes are with him, and a large portion of the Ogallalas; he probably has 2,000 or more well-armed and well-mounted warriors in these late fights.”

In the 1941 movie, They Died with Their Boots On, a fictionalize account of Custer, he tells one of his soldiers on the eve of the battle that “we are to be sacrificed.” Which, given Grant’s orders to pursue the Indians, may not have been far from the truth.

There is still speculation on the battle. What would have happened if Reno and Benteen had got to Custer?

An article in the Cheyenne Weekly Leader, July 15, 1876, might have the answer to the debate.

“When Custer came in sight of the 1,800 lodges, in village of upwards of 7,000 inhabitants, he swung his hat and said ‘Hurrah! Custer has struck the biggest Indian village on the American continent!’ Halting only for coffee, he pushed forward at a rapid gait, took five companies for his personal command, gave Reno three, left four in reserve under Benton, and sailed in. Dr. Porter believes the result would have been the same had Custer charged with his full regiment, only the massacre would have been more terrible.”

Every soldier on Last Stand Hill was killed. Custer’s family suffered a heavy loss. Custer was killed as well as two of his brothers, Thomas and Boston, one nephew, and a brother-in-law. The total US Cavalry casualties included 268 dead, including four Crow Indian scouts and at least two Arikara Indian scouts, and 55 severely wounded (six died later from their wounds).

Historians also point out that Custer’s men were rather under-armed with old Springfield rifles which tended to jam when the barrels got to hot, and the firing was slowed by soldiers having to pry spent cartridges out before reloading. The Hollywood version, showing the cavalry slashing away with sabers, is a myth. Most of the sabers were packed away with the supply train and were not used in the battle. Although repeating rifles such as the Spencer, Winchester and Henry since the Civil War, the Army decided to use a single-shot system. The Indians, while armed with bows and arrows, were also armed with repeating rifles, either stolen from soldiers, or legally traded for, or purchased from traders.

However, most historians agree that, although the rifles may have played a role in the defeat, the real reason for the Custer Massacre was that there were just too many Indians.

In the aftermath of the battle, there was an all out war against the Sioux. People were outraged that the Indians could massacre so many of their fellow Americans. Newspapers played up the need to rid the country of the Indians. Poems, like the snipped from a longer poem in the Cheyenne Weekly Leader, July 15, 1876 Little Big Horn: June 25, 1876. “Three hundred men marched gallantly on, with Custer at their head, at the end of the hour, the fight was done, three hundred men were dead. Weep, fathers and mothers throughout the land.. For the fallen brave in battle…” were written to celebrate those who died. Libby Custer, General Custer’s widow, kept his memory alive in books and speaking tours about her famous husband.

Even with the victory at the Little Big Horn, Sitting Bull was loathe to give up his fight against the white man. Cheyenne, Wyoming Leader, June, 27. 1878. “SITTING BULL . An Interesting Story by a Missionary. The noted missionary of the Sioux nation. Father J. B. M. Genin, has arrived at Bismarck from his prolonged visit to the hostiles across the line. Father Genin arrived at Sitting Bull’s camp alone last August, and up to the 15th of May prosecuted his missionary labors. He has been with the Sioux since 1867 and has personally known Sitting Bull ten years. Sitting Bull calls him his brother, so strong is their friendship. When Father Genin left him the old warrior, who is really only 38 years of age, presented the bearer of the cross with the war mare that he rode in the Custer massacre; also two stone tomahawks of warriors who claimed they had killed respectively eleven and twenty-seven soldiers with them in the Custer disaster. They valued them as great treasures, but their love for their priest forced the sacrifice of parting with them….(Sitting Bull told Genin), “Tell them I am quiet, and will not fight unless I am compelled to. I only want! one thing; I want to go back on my own land, the Yellowstone, where I can I get plenty to live on. I want none of their goods or money.” Father Genin says we must let them have the country, north of the Missouri orv there will be war, the worst in the annals of our country….. Sitting Bull is strong, and the Father says Americans wrong themselves when they under estimate his fighting strength. He can’t take the United States, but, if provoked, he can give them many bullets and a very unprofitable warfare. He has not made up his mind to accept the terms of any reservation proposition.”

In 1881, Sitting Bull returned to the United States and surrendered to the army. He worked for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, and later returned to the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota, where he was shot by a Lakota policeman.

Although the Battle of the Little Bighorn took place 145 years ago, it still lives on in memory, in books, and movies and songs, including the stirring music of ‘Garryowen’ the regimental marching song of Custer’s 7th Cavalry.

(The Little Big Horn Battlefield is a National Monument at Crow Agency, Montana. It has a battlefield tour and a visitor center with a small museum.)

Fred Eans

June 26, 2021 at 5:19 pm

Being born pre WWII, my grandfather was born just five years after this fray. A kid could not keep from admiring Gen. Custer. But also as a kid, the actor Errol Flynn became the warrior Custer, and later when I saw his picture, I remember being disappointed a little, but that is life. His wife lived up to her high standard. Thank you.

William Borner

October 24, 2021 at 3:11 pm

I would like to see some type of movie and story about this legendary battle of Lt Colonel Custer and Sitting Bull. Their really hasn’t been much on this story.