News

Big Nose George Parott, Outlaw Who Met a Gruesome End

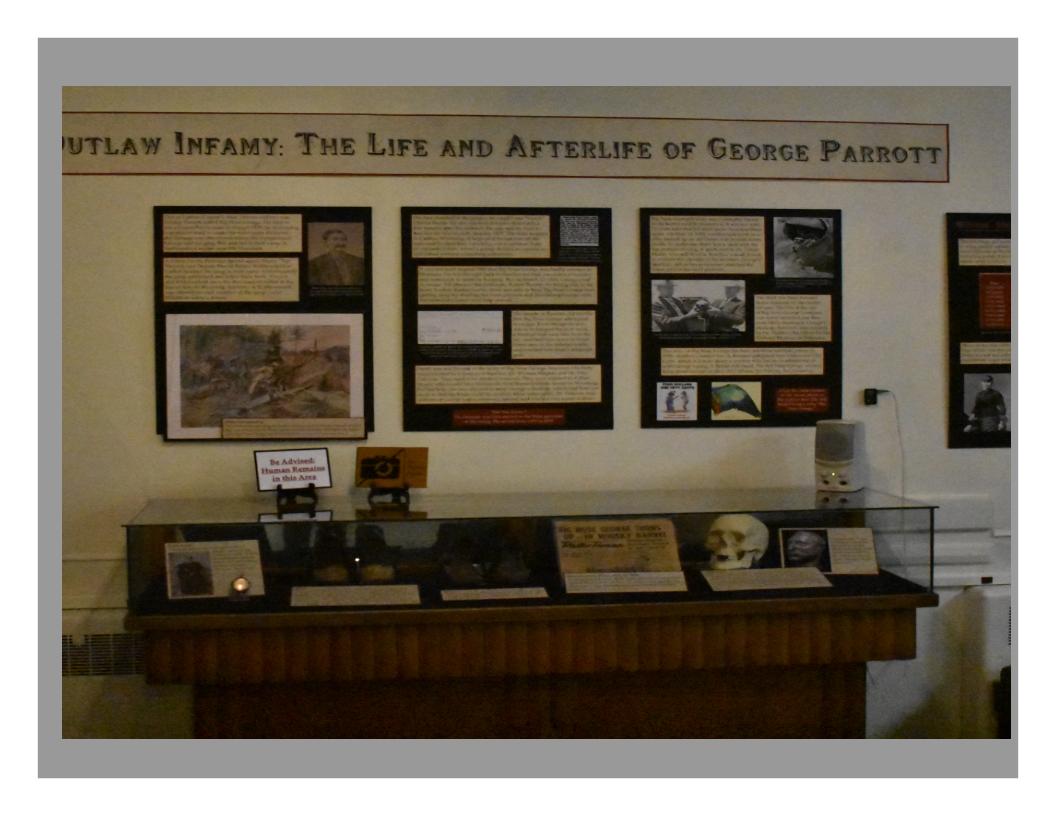

(Photos taken by C Vannoy, displays at Carbon County Museum, Rawlins, Wyoming. Thanks to them)

Although Big Nose Geroge Parott mostly operated around Rawlins, he often hid out at Frank James’ Little Goose Cabin in the Big Horn Mountains. James and Big Nose George even formed an outlaw gang in the Powder River Country.

According to the book, Big Nose George, His Troublesome Trail by Mark E. Miller, (2022 by High Plains Press) George also had a cabin near the Fort Fetterman to Fort McKinney stage road.

O.P. Hanna, one of the early settlers in Big Horn, Wyoming, tells about the time he saw, and almost captured, Big Nose George. This from the Sheridan Post, October 23, 1921 – A merchant by the name of A. Trabing, from Laramie City, put some log buildings on Crazy Woman and laid in a stock of general merchandise. Mr. Trabing had gone back to Laramie and left his manager in charge. One evening four or five men where in there talking, and someone stepped in the door and the command was heard, “Hands Up.”

The leaderof the gang (Said to be Jesse James) took over one thousand dollars worth of goods, bade the manager good night, told him he had very nice stock of goods and that he might count on them as some of his regular customers.

Two days after the robbery, I (Hanna) was hunting up Little Goose Creek, had wounded a deer and was trailing it through the brush, when I ran into a camp in the thickest timber. There was a gang of thieves looking over the goods stolen at Trabing’s store.

I kept moving backward and played it so well I got out all right without them suspecting me, but they warned me to keep mum.

That night I went to Fort McKinney and sent a message to Laramie that I had found the road agents’ camp. I returned to my ranch and that night Big Nose George, one of the gang, rode up and wanted to know if I had any liniment, as his horse had fallen on him and hurt his knee. I gave him some liniment and he stayed over night. There was a three thousand dollar reward for him and I knew it; could have captured him easily but had no place to put him. After I sent the notice to Laramie the authorities sent out about twenty men. I They rode night and day, but when i they got to Little Goose the gang had flown. They got wind that the posse was coming. They went to the Yellowstone country.”

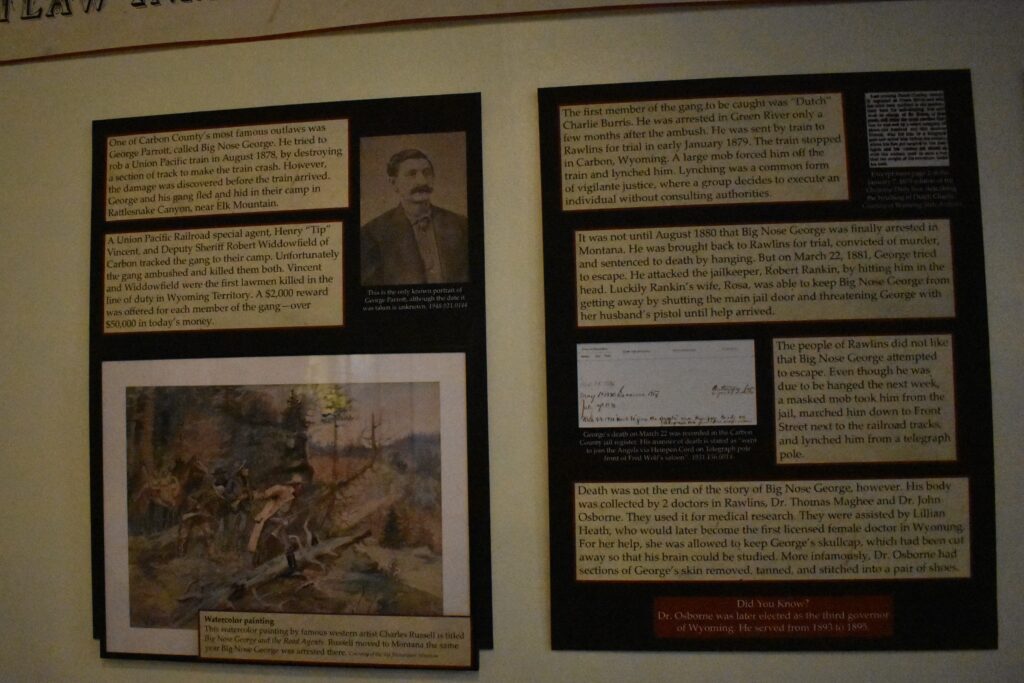

Big Nose George and his gang operated throughout Wyoming, robbing stagecoaches, trains, and isolated stores such as the Trabing store.

And this article from The Sheridan Post, September 8, 1911 – The Old Frontiersman. J. G. Rankin is his name “Jim” to those who know him. He seventy-two years of age now: but he wasn’t always that old.

In 1876, the people of Carbon county needed a sheriff. They needed a good one and they chose Jim Rankin. They kept him in office covering 1876-1880, and again elected him for 1885-6. One incident in his eventful career will show what sort of a man he was, and it happened in 1878. The overland trains were a great temptation to the outlaws of the West, and to hold them up and go through the passengers was about the only source of revenue they had.

One particular knight, called Big Nose George, was the terror of the West at the time. His operations were carried out in Montana, Wyoming and adjoining states, and he had them all buffaloed.

Railroad officials, territorial officials and all, turned pale at the mere mention of the name of B. N. George. Yes, they all turned pale— all but one, and that was Jim Rankin. Nothing could change Jim’s complexion or put fear into his heart. It was inevitable that this noted outlaw, who was a man of great courage himself, and the noted outlaw taker, who had a countrywide reputation for bravery, should one day meet and measure steel. They met, and this is how it was told by old Jim as he sat in a big arm chair in The Post sanctum the other day, surrounded by several old friends who knew him in the day of the occurrence.

“It was like this,” said Jim. “This Big Nose George, with eight of his gang, came down to Rawlins in ’78, from the Montana country, for the purpose of holding up the U. P. trains. They did the trick all right, at a bridge just east of the town. I don’t recall now just what loot they did get, but it was quite a haul. In the preliminary skirmish they killed a couple of men in my posse, and before they could be located in the hills, succeeded in slipping out and making good their escape to Montana. “The more we thought about the matter the hotter we all got, and the more we wanted to get hold of Big Nose George.

“The railway officials thought it too hazardous to pursue the band, but the county officials thought otherwise. “Accordingly, I journeyed to Miles City, passing through your Sheridan County and following down Tongue river to Miles. There was not much Sheridan here in that day.

The article continued saying that at Miles City: One of George’s lieutenants waited upon me and asked if I proposed to take George, “That’s what I came here for,’ I replied. ” ‘Then you’ll have a h__ of a time.’ said George’s friend, “and we’ll never let you get out of the country with him.’ “‘

All right!’ I said, ‘You will learn later who is running this country — you fellows or the representatives of law and order. And my advice to you follows is to have a care. If things are going to happen ’round here, we will try and take care of ourselves and you fellows at the same time.’ “

The emissary departed. “The gang got pretty well steamed up later in the night, and when they came down street, the Montana sheriffs sorted George out of the party and placed him under arrest. “No resistance was offered. The Montana officers turned the prisoner over to me with the statement that I was responsible for his safe keeping. “I undertook the job. I placed the prisoner in irons and gave him a shakedown in a lower hallway and mounted guard over him.

“The next morning, shortly after breakfast, a little Yellowstone river steamboat came wheezing along, and together with the Montana sheriffs we went to the landing.

“When the stage plank was run out it was immediately blockaded by the friends and sympathizers of George. Before the gang had time to think I drew my gun and informed the crowd that I would be glad to mow a path over that stage plank if the boys insisted, and they only had one single minute to consider. I ordered the captain of the craft to haul in the stage and back out, which he did promptly.

“There was some discomfiture on shore at our sudden move, but no shot was fired. My prisoner and myself were safely in the cabin by this time. At Bismarck I had some trouble with one of George’s gang, but the captain of the boat and myself quietly disarmed him and as quietly dropped him overboard and instructed him to swim for the shore.

“Continuing the journey to Omaha by river, and by rail to Rawlins, no incident occurred worth mention. At Rawlins the whole city turned out to welcome us. It took an ‘hour or more to get from the station to the jail.”

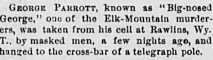

“One night, when all was quiet and most of us were out of town or engaged elsewhere, a mob of mighty good men took George from the. jail and hanged him to a telegraph pole That was the end of Big Nose George.

But, that was not the end of Big Nose George. His death was actually more hair-raising that his exploits when he was alive.

The Saratoga Sun, August 3, 1916 – (this from a longer story about the outlaw) Big Nose George’s right name was George Parott, and his lynching was the outcome of an attack on Jailer Bob Rankin while being held in jail awaiting his legal hanging, for which he was sentenced for the killing of Vincent and Widdowfield. (Vincent was a Union Pacific detective and Widdowfield was a deputy who went to bring George to justice near the Medicine Bow country.)

The story is told by old timers of the skinning of this man, his hide tanned. (Actually, only the chest and thighs were skinned) The writer has it first hand that the report (is correct) and his body was placed in an old abandoned cellar. We have seen a piece of the tanned hide and have been informed that one Denver man has a pair of moccasins made out of some of the hide. Another story is to the effect that his skull is an ornament on the desk of a former Rawlin’s business man. Be what it may, it is now grewsome (sic) to the present generation.

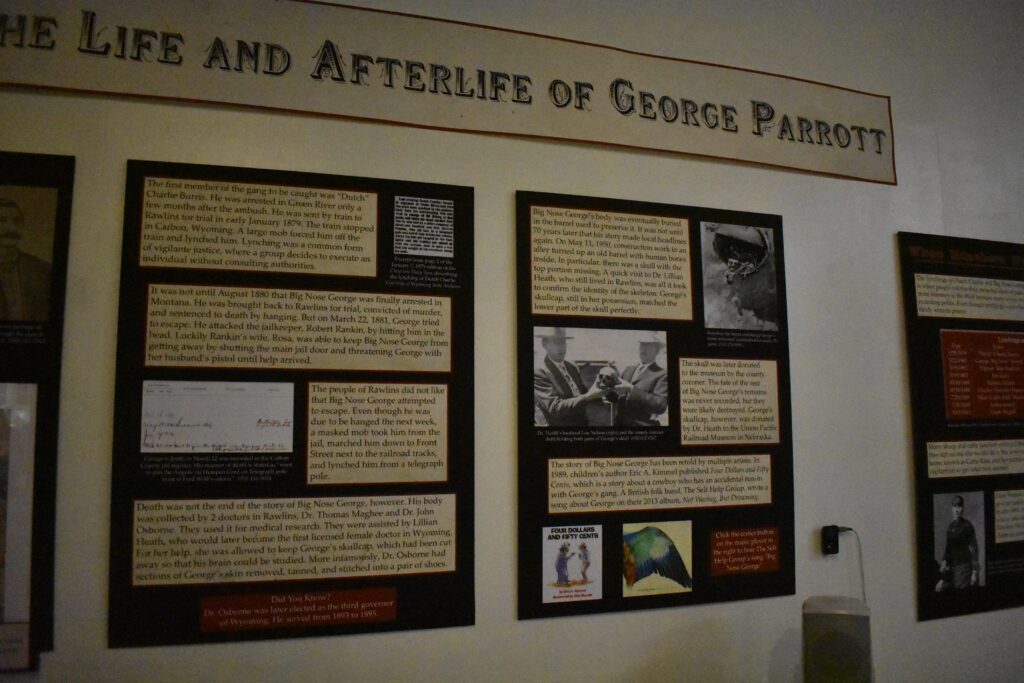

According to various accounts, Dr. Osborn made a pair of shoes out of the tanned hide, as well as a medical bag. He cut the skull cap off to examine the outlaw’s brain, and gave the skull cap to 16-year-old Lillian Heath, who was a medical assistant to Dr. Thomas Maghee, who helped with the examination, as a souvenir. Later she became the first licensed woman doctor in Wyoming.

Heath kept the skull cap for years using it as a door stop, and her husband used it as a tobacco pipe ashtray. Later, she donated it to the Union Pacific Museum in Omaha, Nebraska.

According to an oft-repeated story, Osborne wore the shoes at his inaugural ball when he was elected Governor of Wyoming in 1892. These shoes are now on display at the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins, Wyoming, as well as a replica of George’s skull.

For years, the location of the rest of Big Nose George’s remains was a mystery. Then, in 1950, a barrel of bones was unearthed by a backhoe operator in downtown Rawlins. The skull had the skull cap removed, and the skull cap owned by Heath fit the skull precisely, proving the bones were those of Big Nose George Parott.

A murderous outlaw, who operated in the Powder River Basin and around the area of what is now Sheridan, met with a gruesome fate near Rawlins in 1881.