News

Jim Bridger Part 3: Guide and Army Scout

In part three of Jim Bridger’s story we will see his contribution to the Sheridan area and the part he played in Red Cloud’s war.

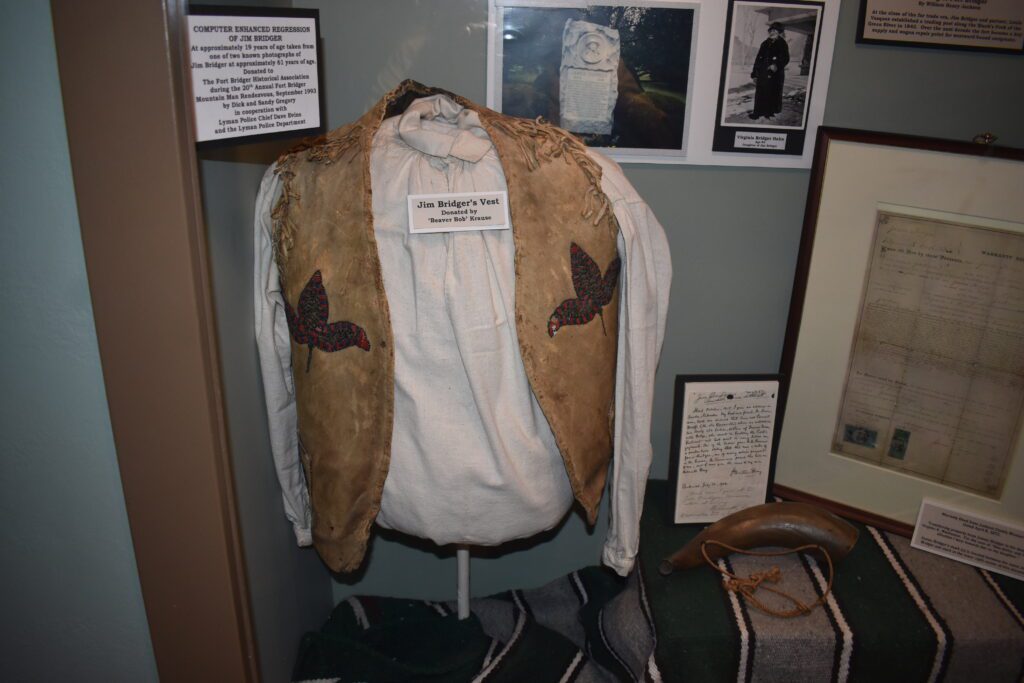

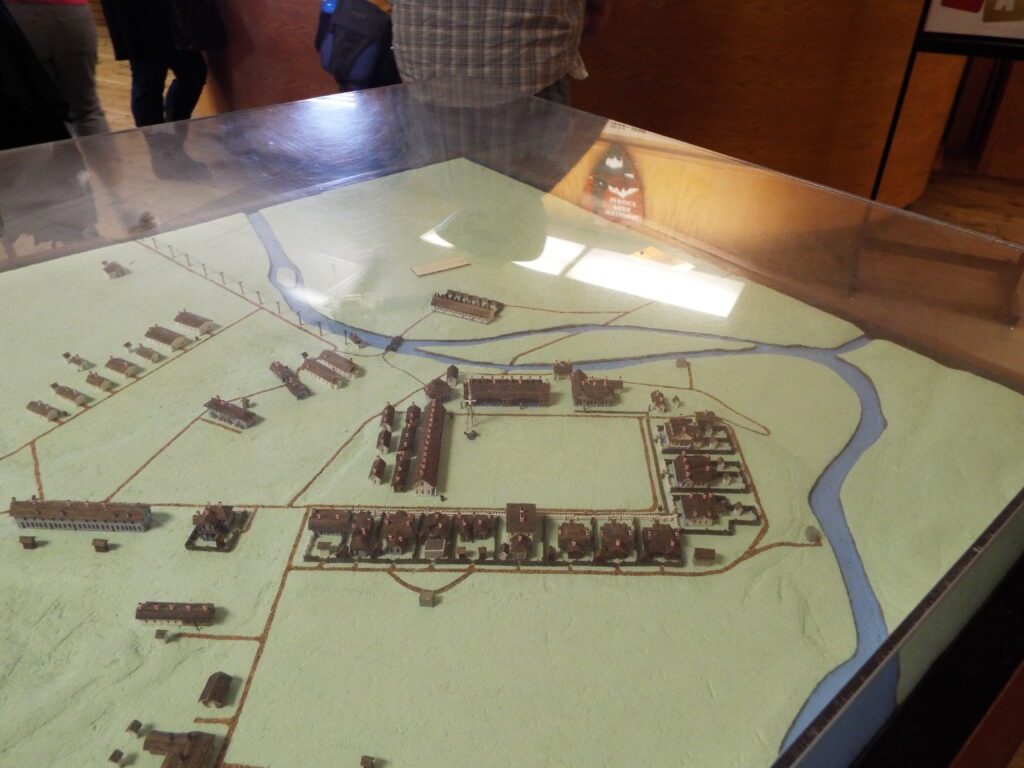

After the Mormons burned his trading post on the Green River, Bridger leased the land to the army, and they built and garrisoned a fort where his trading post had stood. Many of these buildings still stand today at the Fort Bridger State Historical Site.

Bridger also guided gold seekers, and suggested that his trail, the Bridger Trail, which avoided the Sioux hunting grounds, was a safer trail then the shorter route that John Bozeman recommended.

This from the Cheyenne State Leader, July 1917. James was undoubtedly the most celebrated pathfinder in the Northwest. The Bridger trail to Montana, although long since abandoned, was once the principal route to the gold fields of the territory from the states. The trail exists no longer except on old-time maps, but there is monument to Bridger’s name and fame that will last as long as the earth itself. That is the beautiful towering Bridger Range of mountains, near Bozeman, that skirts tho beautiful Gallantin Valley’s eastern border for distance of nearly fifty miles

Bridger, in what he often referred to as his retirement plan, became a scout for the U.S. Army during Red Cloud’s War.

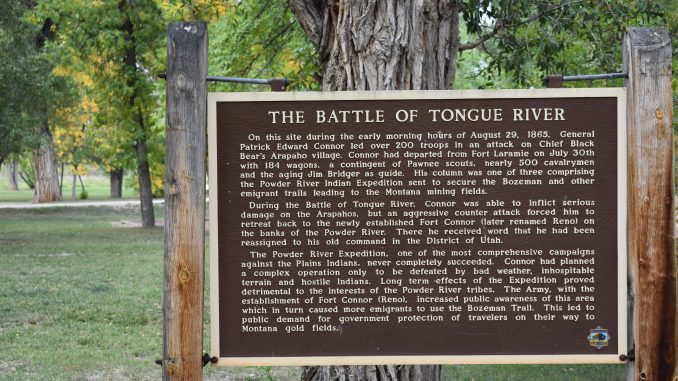

One commander who enlisted Bridger’s services as a guide was General P.F. Connor, whose Powder River Expedition brought him, guided by Jim Bridger, to the Sheridan area.

From the Laramie Republican, July 17, 1900. – Last Battle of the Civil War was fought near Sheridan – A Strange Story Related by Captain H.E. Palmer:

Strange as it will be to all but a very few— stranger than all to a vast majority of “the old soldiers”— the last battle of the civil war was fought in what Is now the state of Wyoming, a few miles from the present city of Sheridan, (It was near the present-day town of Ranchester.)

Even thought government records are defective ‘regarding it, giving the date of August 28, 1865, instead of August 29, 1863. It was the last battle from 1861 to 1865, inclusive, in which volunteer soldiers took part.

The story was told by Captain H. B. Palmer, then acting on the staff of General P. F. Connor, who said: Thirty-five years ago today, I was near the corner of Bullock’s sutler’s store at Fort Laramie talking to James Bridger. Major Bridger, as he was called, and Kit Carson were the two best guides that up to this time had made their reputation on the plains and in the mountains of what was known as the “far west.” Bridger was Fremont’s chief guide from near the Missouri river to California by the central route; Carson guided him twice o’er the southern route.

I was making a verbal contract with Bridger to guide the “Powder River Indian Expedition,” at $10 per day and rations. After he had agreed to accept my offer and my conversation was finished, I was about to leave him when a well-dressed, bright looking sergeant of the Eleventh Ohio cavalry, who had enlisted from an Ohio college, stepped up and said, “Is this Major Brldger?”

The major answered, “Yes.” The sergeant said, “You have been In this country a long time, major?” “Well, yes; forty-three years,” answered Bridger.

“You have seen many changes in this country in that time,” queried the sergeant. (Note please that at that time Fort Laramie was an old wooden fort, not a building or fence off the small reservation. Just a lodging place in the wilderness, the nearest habitation being the few ranches from ten to twenty miles apart on the South Platte river, about 150 miles away).

The major in response, after rolling his huge quid of tobacco to the other cheek, said, “Well, yes; do you see that there peak over there?” (pointing to Laramie Peak, ninety miles away). “Yes,” said the sergeant.

“Well,” remarked Bridger, “when I first come to this country, forty-three years ago, that thar peak was a hole in the ground.”

But, I have been asked to tell you of the last battle of the war of 1861 to 1865, the last battle where volunteer troops who had enlisted to put down the rebellion were engaged. In the summer of 1865, there were over 17,000 volunteer troops in service in the district of the plain, General P. B. Connor, commanding.

After having fought for the preservation of the union, these men had to do valiant service on the plains, fighting merciless Indians. There were no newspaper correspondents with the troops on the plains, no telegrams were flashed over the wires, for there was only one wire and that was along the Platte. Our service was at times 300 miles from the nearest telegraph station.

The Powder Expedition was for two months beyond the reach of mall or messenger. On the morning of August 27, 1865 while riding in the extreme advance of our column with Major Bridger, the guide, when we reached the top of the divide between the waters of the Piney and what is now called Prairie Dog creek.

The magnificent view from the top of this hill, or divide, was enough to cause us to halt and view the country, Major Bridger with his hand shading his weak and worn-out eyes, I with a fine field glass to sweep the horizon. For five minutes or more we sat on our steeds and silently “looked the landscape o’er.”

The major was the first to break the silence by remarking, “Do you see those ere columns of smoke over there ‘by that saddle,” (a low divide near where the village of Parkman is now located). I looked and for the life of me could see no columns of smoke, which of course would indicate an Indian village.

I said to Bridger: “We will dismount and wait for the general,” who was just in rear of the advance guard. When Connor came up, I reported that Major Bridger had discovered an Indian village. “See the columns of smoke over yonder by that saddle?”

The general leveled his field glass at the spot mentioned and after a long look remarked: “There are no columns of smoke there.” Bridger mounted his pony and rode on. I followed a few moments later and, overtaking him, heard him swearing about the “dern paper-collared soldiers” telling him there were no columns of smoke.

General Connor called Frank North, who commanded eighty Pawnee Indians, who were our advance guard, and directed him to go with seven of his best men to see if there were any Indians near where Bridger thought there was. We marched down Pencan creek, now known as Prairie Dog creek, a good day’s march, and camped; next day a long day’s march beyond the mouth of Prairie Dog, down Tongue River.

Just after sunset of this day two or three Pawnees who went with Captain North toward Bridger’ columns of smoke on the August 27, came into camp with the information that Captain North had discovered an Indian village.

I had never been baptized with Indian blood, and never had taken a scalp. I begged the general that I be allowed to accompany him the glorious work of annihilating the savages. The general granted my request. The men were hurried to eat their supper, just then being prepared and at 8 o’clock p. m. we left camp with 250 white men and eighty Indian scouts as the full attacking force.

They found the village and attacked it, and it was an Arapaho village, not a Sioux village. They did kill several Indians and captured several Indian ponies.

The son of the principal chief (Black Bear) was killed, sixty-three Indians were lain, and about 1,100 head of ponies captured. While we were in the village destroying the plunder, most of our men were busy remounting. Our own tired stock was turned into the herd and the Indian ponies were lassoed and mounted; this maneuver afforded the boys no little fun, as nearly every instance the rider was thrown or else badly shook up by the bucking ponies. The ponies appeared to be as afraid of the white men as our horses were afraid of the Indians. If it had not been for Captain North, with his Indians, it would have been impossible for us to take away the captured stock, as they were constantly breaking away from us, trying to return toward the Indians, who were as constantly dashing toward the herd in the vain hope of recapturing their stock.

Bridger and the Pawnee scouts told the soldiers how the Indians rode the ponies, mounting on the right side instead of left, and they finally were able to ride the Indian horses to save their own mounts.

Later, Bridger spent some time at Fort Phil Kearny with Carrington, and he told Carrington that the soldiers had no idea how to fight the Indians. He once told Gen. Henry Carrington, “General whar you don’t see no Injuns, thar they’re startin’ to be thickest,” and the general found it good advice. –The Riverton Review and the Riverton Republican, April 1922.

At Fort Phil Kearny, Bridger said this about Fetterman, for whom he had little respect of his Indian fighting skills.

A few days later, Fetterman and his men were massacred on December 21, 1866.

Fetterman Monument

By the end of Red Cloud’s War, Bridger was getting old, and he had lived a hard life. The hardest thing to bear was when his sight began to fail. By 1875 he was totally blind. He had been married three times, and had several children, some of which he sent east to school. In the early 1870s, he lived with his daughter Virginia, his only living child. He died on his farm in Missouri in 1881, at age 77.

In The Wyoming Press, Evanston, Wyoming, December 1904 Monument for Jim Bridger. Kansas City, Mo., Dec. 4.—The bones of James Bridger, the famous scout and discoverer of Great Salt Lake, will be brought from an obscure grave on a farm ten miles south of this city for final burial in a local cemetery tomorrow.

A granite monument seven feet high and three and a half feet thick, with a life-sized bust of Bridger, will mark the grave. It probably will be unveiled next Sunday. Mrs. Mary Leightle, Bridger’s granddaughter, will unveil the monument.

The expense is being borne by General Granville M. Dodge, who, as an engineer of the Union Pacific railway, was indebted to Bridger for the discovery of a pass through the Rocky Mountains through which the railway was built. The town of Ft. Bridger, 50 miles east of Evanston in this county, was named for Jim Bridger and there are still a few pioneers in this city and the Bridger country who knew and associated with him. He was, as the above says, a famous scout and discoverer, being a companion of Kit Carson and other daring explorers.

Bridger’s legacy lives on in the names of many places. There is Fort Bridger Historic Site in the town of Fort Bridger, Wyoming; there is a Bridger, Montana and a Bridger, SD. We have the Bridger Mountains in Wyoming and in Montana; Bridger Bay in the Great Salt Lake; the Bridger-Teton National Forest, Wyoming, and Bridger Pass among many others.

Jim Bridger, undeniably one of the most famous figures not only in Wyoming and the West, but in the entire United States. Blacksmith, trapper, explorer, storyteller, guide, pathfinder, and visionary, without him, the story of the Westward Expansion might have been written very differently.