News

History: Horse Cemetery at Little Big Horn Battlefield

At the Little Big Horn Battlefield outside of Crow Agency, Montana, there is the Custer National Cemetery, where the dead from the Fetterman fight are buried, along with many of the dead from the Custer Battle, as well as many other veterans and Indian scouts.

On the battlefield there is a monument to Custer’s men who died on Last Stand Hill. After the battle the men were buried where they fell, but later the remains were re-interred to various locations. In 1890, Army personnel erected 240 white marble markers that were erected at the locations where the fallen soldiers were found.

The Daily Boomerang, Laramie, December 22, 1884, had this item about the marker.

The monument placed on the spot where General Custer’s command was massacred, near the Big Horn river in Montana, is reported to be rapidly disintegrating under the influences of the weather. Some time since a high iron railing was put up to protect the memorial from injury at the hauds of relic hunters, to whom nothing is sacred, but the action of the sun, wind and rain proves even more destructive than were the chippings of the vandals.

There is also a monument to the Native Americans who fought to keep their homelands.

But, soldiers were not the only ones who are buried on the battlefield. Across from the monument honoring the men of Custer’s command, there is a small, easily missed marker that reads, “7th Cavalry Horse Cemetery.”

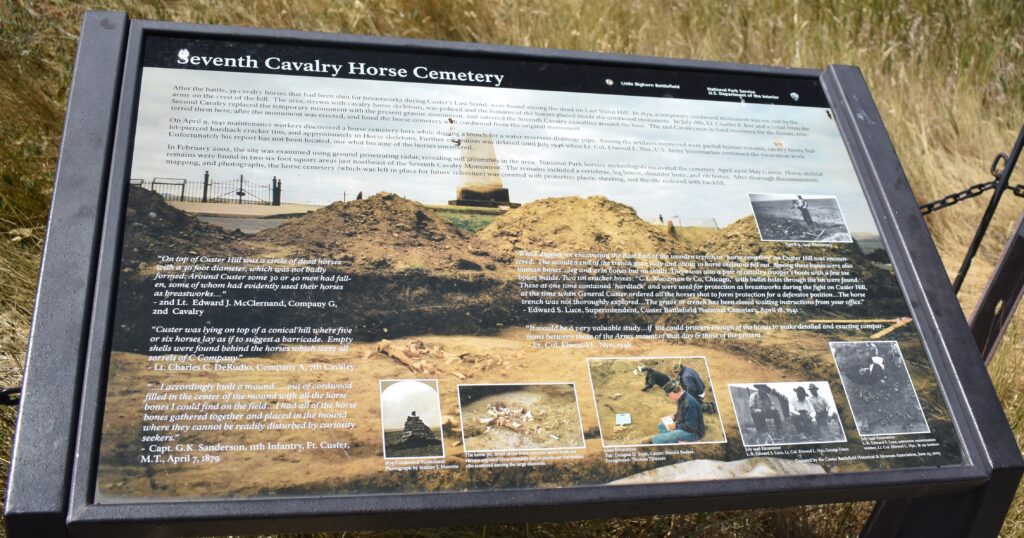

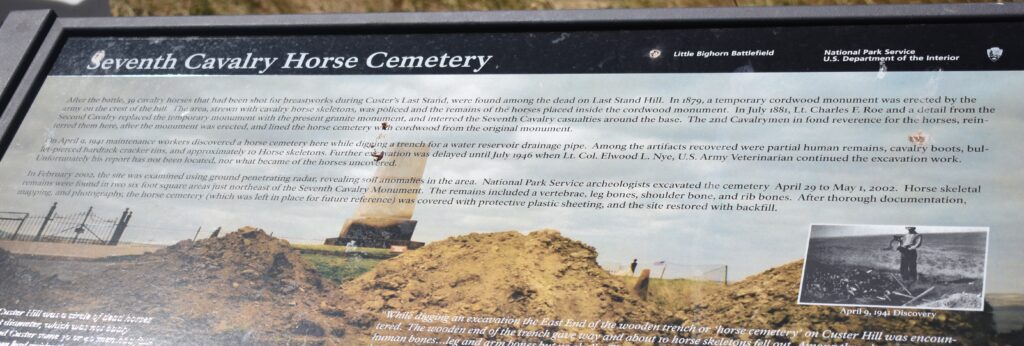

On the information sign, it describes how it came about.

After the battle, the 30 cavalry horses that were shot to form breastworks for the soldiers were found among the dead on Last Stand Hill. In 1879, a cordwood monument was erected, and the horse bones were placed inside of it.

Later, the cordwood monument was replaced by a small granite marker.

Although the ‘Horse Cemetery’ was not found in the old newspapers, there were several stories about the how the cavalrymen loved and depended upon their mounts.

The Cokeville Register, June 14, 1919 – Perished with their riders: Horses of Custer’s Command Died as Bravely as the Soldiers They Carried. Stories of equine courage and fortitude displayed in the late war recall that of a famous horse, Comanche, sole survivor of the Custer massacre. Comanche was the mount of Captain Keogh, a relative of General Custer. He was found shortly after the massacre about a day’s journey from the battlefield. Suffering from seven bad wounds and very weak from loss of blood. It was at first despaired of getting him back to camp. But the soldiers carried him on a litter constructed of strong poles and army blankets. Given the best of treatment, he fully recovered to receive an honorable discharge.

Custer’s men used the bodies of their horses for barricade against the Indians. As they went into action on horseback every horse was saddled, but when Comanche was found he was without even a bridle, so it was supposed that the Indians, believing he was too badly wounded to recover, stripped him and left him to die. Every other horse was found in the heaps of the slain.

Diorama at the Custer Battlefield Interpretive Center

This story was from The Lusk Herald, January 7, 1892, which tells of Keogh’s devotion to his mount, the famous Comanche, who will be featured in the history column at a later date. – Death Of Comanche. The Only Thing of Custer’s Command that Came Out Alive There died at Fort Riley, Kan., recently, the most famous horse in the West in many respects. It was Comanche, the war-horse that was the only thing on Custer’s side that came out of the massacre in June, 1876, alive. Comanche had never been under saddle since, and lived at ease until death by old age, the pet and care of the Seventh Cavalry. He was twenty-five years old, and was visited by sight-seers from far and near during the last years of his life. Professor Dyche, of the State University, secured the skin and skeleton for mounting, and will prepare them for exhibition at the world’s fair.

With Custer was Captain Miles Keogh, who rode Comanche. The horse had been in several battles and could stand fire like a post or run like a mustang. At first the soldiers seemed successful, but then the terrific fire told on their ranks. Captain Benteen and Custer were driven slowly before the great force of the enemy and waited for Reno to attack the rear, but he did not come. Leaving Captain Keogh on a lower ridge, General Custer and his men ascended the crest of the knoll to which they were driven and there made his last stand. Keogh, seeing his men exposed to the fearful rain of bullets, gave the order to the men to kill the horses and take refuge behind their bodies. The order was obeyed. He still rode Comanche — and here there is a variance as to the manner in which the escape of the animal occurred. Some Indians say he broke away and ran, but the more popular version is that his master being unable to consider the thought of taking the life of the beast who had served him so well, dismounted and giving the animal a stinging blow with his sword, drove him away and turned his unprotected front to the foe.

This story in the Northwestern Livestock Journal, December 10, 1886, tells about the horses used for cavalry mounts, and how much equipment they were expected to carry on campaigns.

(this was from a much longer article about the benefits of western horses for use in the plains cavalry). When in active service United States cavalry horse carries a cavalryman weighing about 150 pounds, saddle, bridle, saddle blanket, saddle bags and contents, nose bag, side lines, lariat, picket pin, canteen of water, poncho, blanket, carbine, pistol, 100 rounds of ammunition, twenty-four rounds of extra pistol ammunition, three days’ rations, curry comb, horse brush, set of horse shoes, some horse shoe nails, change of underclothing and an overcoat—in all weight of something near 300 pounds, distributed as equally as possible on each side. It will be seen by the above that it requires an extra good horse to carry all that weight and travel good distances day by day. Now, let us see what standard of horse is demanded for this service. Referring to “Regulations of the Army of the United States,” folio 35, article XXX., purchase and care of public animals, par. 293. The following specifications will govern in purchasing horses and mules for the military service (G. 0. 17, 1876) Cavalry horses—to be geldings, of hardy colors, sound in all particulars, in good condition, well broken to the saddle, from fifteen to sixteen hands high, not less than five nor more than nine years old, and suitable in every respect for cavalry service.

It continues

Whoever reads the above carefully will see that we have now an abundance of western horses that will fill all the above requirements. Western horses are not now what they were ten and fifteen years ago. They have been bred up all the time, till now western horses are nearly thoroughbred after whatever strain they have been bred from. Beside, the western range-bred horses have hoofs of iron, muscles of steel and constitutions of adamant. Wherever fairly tested, they have done more service and lasted longer than any others. Eastern street railway companies have learned this, and are filling in with western horses entirely.

This story tells about a soldier who was saved from the Custer Battle by virtue of NOT having a horse. It also describes what the ‘saddler’ did. From the Wyoming Star, Green River, Wyoming, June 9, 1905

John Thomas was the sole survivor of General Custer’s expedition up the Big Horn, which was completely annihilated by the Indians, is resident of Minneapolis. He is fifty-eight years old and lives at 8601 Aldrlch Avenue. After reading dispatch in the Tribune stating that William McKee, of that city, claimed the honor of being the last white survivor of the massacre, Mr. Thomas talked interestingly of the events leading up to the massacre and those which followed. “I know McKee well.” said Mr. Thomas. “He was not member of General Custer’s expedition, but was in General Reno’s detachment. There was but one person who escaped alive, and that was an Indian by the name of ‘Curley,’ who is now with the Buffalo Bill show. While I was in the expedition under command of General Custer I was not in the massacre. It was only by accident, however, that I was not.

“When a young man I joined the Indian fighter under command of General Terry. My duly was that of saddler. cared for all of the harness, saddles, and sometimes made myself handy as shoemaker. With the other warriors I was supplied with horse. About week before the massacre the entire expedition was camped on Tongue River. General Terry decided that the forces were to be divided, and 860 men were placed under command of General Reno. General Gibbs, of Montana, was in command of much smaller detachment.

“I was placed under General Custer, and everything was in readiness for the party to start when General Custer came to me and said: ‘John, who is using this horse?’ “I replied that intended to use the horse, to which he said that he wanted the horse for Chicago newspaper reporter. Who insisted on using the horse, when the General declared that he would consider his men a poor lot if they would not know enough to take care of their own saddles and harness for five or six days.

“These were the last words he spoke to me. I gave up the horse to the reporter and was sent to the boat under one of the captains of General Gibbs’ army of scouts. “The reporter did not return, neither did any of the men under General Custer. All were killed in the massacre, and with the exception of the newspaper man and General Custer the men were all scalped. The Indians had great love for General Custer, and for that reason it is believed that they did not scalp him. As for the reporter, they found the papers on his body, and were civilized enough to know that he was not their enemy, but was courier of news.

“I would have been in the massacre had it not been for General Custer taking my horse and giving it to the reporter. After the massacre was under General Gibbs, General Miles was then assigned to succeed General Terry.

The horse cemetery is a tribute to the horses used by the plain’s cavalry. The horses bled and died along with their riders, and a horse could mean the difference between life and death on the Western Frontier.

Meshelle Cooper

August 17, 2024 at 3:44 pm

Very nice story, Cynthia!

A tribute to the battle horses – so very important at the time.