News

Accounts of the Wagon Box Fight

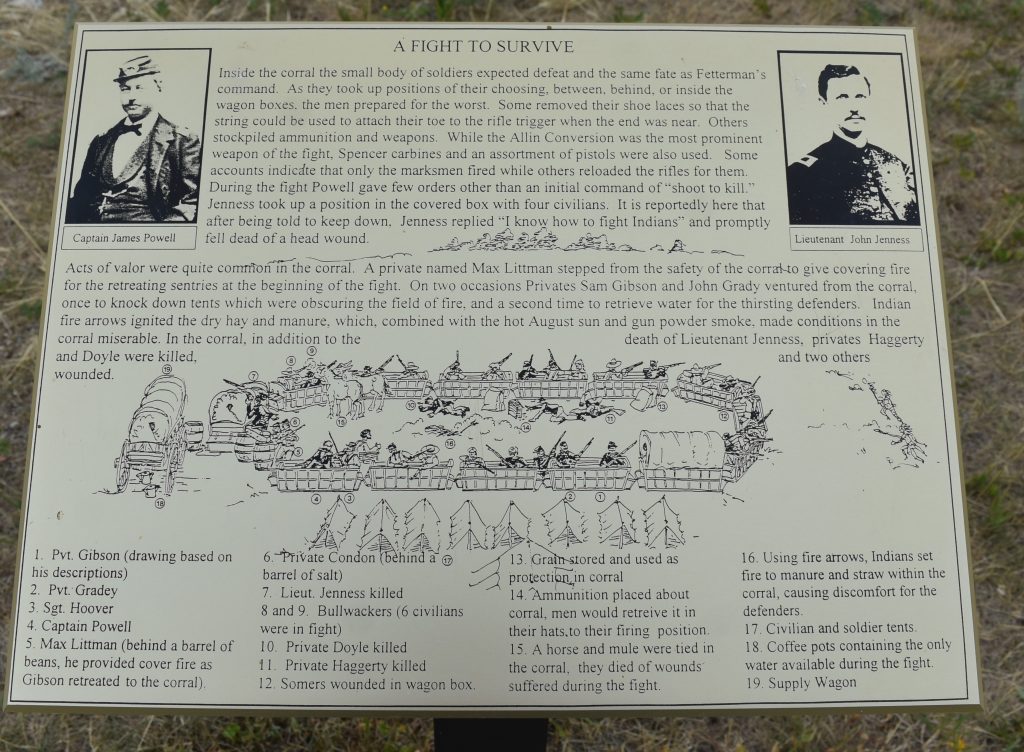

The Wagon Box Fight occurred on August 2, 1867, on an open field between Fort Phil Kearny and the present-day town of Story. It was the last major battle between the U.S. Army and Lakota warriors along the Bozeman Trail. Twenty-six soldiers and six civilians were attacked by several hundred Indians when the party was sent out from the fort to cut wood.

Although greatly outnumbered by the Sioux, the men held off the attack for several hours, until help arrived from the Fort.

In the Sheridan Daily Enterprise on June 11, 1912, there was an account some years later from a Max Littman, who was in the battle. (One account said Littman was a German immigrant, Germans and Irish soldiers made up a lot of the plains army during that time.)

No Trenches Used at the Famous Wagon Box Fight Says M. Littman of St. Louis, Who Participated in the Historical Battle

“There were no rifle pits or trenches used by the troops in the Wagon Box fight, in spite of all the talk to the contrary. I know, because I was there.” This assertion by M. Littman,, a well known manufacturer of St. Louis. Mr. Littman accompanied by Mrs. Littman and their daughter, spent two days in Sheridan en-route home after a tour of the south and west.

This is Mr. Littman’s first visit to the vicinity of the famous fight in August, 1867. Monday he went down to the scene of his historical experience, and readily recognized the site of old Fort Kearney. He was unable to proceed up to the actual site of the Wagon Box fight.

“I was a member of Company C, Twenty-Seventh United States infantry,” said Mr. Littman. “I enlisted in May of 1866 and was sent out west with General Carrington. We proceeded to old Fort Kearney where we made our headquarters. The Wagon Box fight took place from 7 in the morning until about 2 o’clock in the afternoon on August 2 .

I was with my company and we constituted the guard at the half way point between Fort Kearney and the timber. We were out to guard the wood cutters who had the contract for furnishing us with wood. To make our camp we placed the wagon boxes about in a circle of perhaps seventy feet in diameter. The oxen were put inside this and our tents were outside.

“The Indians charged down on us early that morning. I saw them first and remarked to a comrade, ‘Well, here comes three thousand German cavalry.’ We soon saw what they were and immediately got within our fortifications. There were no trenches or rifle pits. We buckled on our belts and got ready for action.

We each had three thousand cartridges, and there were twenty-seven of us. Myself and Jim Condon, the baker — and a good one, too— did not get behind the boxes, but instead got down on our stomachs behind two heavy ox yokes, one on top of the other. There was a barrel of salt and a barrel of beans also near by. After the fight, I found fifty-seven bullets and arrows in that old ox yoke, everyone of them I bunched together and within a foot of where my head was. That is how near I came to getting killed.

“The Indians swooped down on us, about three thousand strong. (There is a lot of controversy about how many Indians were in the battle, but this was his account,) We lost two privates and Lieutenant Jenness during the fight and the lieutenant was the first one killed. He was standing up and had just remarked, ‘Well, boys, they are coming, but I don’t think I will last long. But — ‘. Just as he said that last word a bullet struck him, and he fell dying. The Indians circled around and around us, and now and then there would be a straight charge. They got pretty close at times, as afterward we found one dead Indian within fifteen feet of the corral.

“We didn’t have to take aim at any particular Indian. We just had to fire at the mass they were so thick, and we were sure of killing or wounding some of them. We estimated that during the fight we killed about 300, but old Red Cloud himself years afterward admitted that we had killed and wounded over 1,100 of his braves.

He added, “I always believed that the Wagon Box fight was the turning point in the Indian wars. They first learned there just what the white soldiers could do.”

“The main body of the troops up in Fort Kearney could hear the firing down in our direction, but couldn’t get out. (Another account said they saw the black powder smoke.) The Indians hemmed them in, intending to get us first. They had already charged on the wood haulers and these men fled into the mountains. Some of them were killed and, the others got back after a while.

“Our camp and the spot where the fight occurred was on top of a little knoll about a half mile or a little less up from Big Piney. In fact we were between Big and Little Piney. We were about two and a half miles from Fort Kearny.”

The story ended there about the fight, and Littman didn’t mention that the soldiers did get there from the fort to relieve the beleaguered wood train.

One reason this battle was so successful for the army was that the Native American’s were used to the army using the muzzleloaders, and they planned to bring up the second charge while the soldiers were reloading the muskets. The new rifles, Springfield Model 1866 and lever action Henry rifles, had cartridges instead of musket balls, and it didn’t take the soldiers any time to reload.

Some of the Native American’s involved in the fight were Crazy Horse, who was one of the decoys trying to lead the soldiers away from the wagon box corral, High Backbone, American Horse and Big Crow. Some accounts say that Red Cloud was watching the battle from the nearby hills and didn’t engage in the battle. Women and children also watched the battle from the surrounding hills.

Another account of the battle from Sheridan Post, October 23, 1921

The Wagon Box Fight took place on the 2nd day of August 1867, about three miles south of the present town of Story, on the other side of Piney. On that day a force of thirty-two men, under Captain James Powell was guarding a wood cutter’s camp near the scene of the battle. Red Cloud, thinking the opportunity a good one, sent 500 Indians against the little band.

Powell however, was warned of their approach by his lookouts and had time to prepare for them. The wagon beds used in hauling wood were made of iron, or were wooden boxes shod with iron of sufficient thickness to resist an ordinary bullet. These wagon beds were hurriedly arranged in a circle, inside of which the thirty-two men took their stand.

They were armed with breech-loading rifles, a new model that had only recently been issued, and Captain Powell, aware of the fact that a cool head and a steady aim was their only hope, ordered that the poor marksmen should keep the rifles loaded for those more expert marksmen to shoot.

They had not long to wait until the yelling hordes appeared, evidently expecting an easy victory. On they came until near enough to make the aim of the little band behind the wagon boxes certain, when the breech-loading rifles began their deadly work. Not a bullet went wild and the Indians recoiled before that deadly fire.

When Red Cloud saw the wholesale slaughter of his best warriors, he decided to change his tactics. Dismounting his men, they crawled forward through the shrubbery, hoping to get near enough to the defenders to carry their position with a rush.

But the attempt was a failure. Every time an Indian exposed himself, this earthly career was cut short with a bullet from the rifles that were never empty, while the balls fired by the Indians flattened against the iron wagon bodies and were thus rendered harmless.

More Indians were brought up, but Red Cloud’s entire force proved unable to conquer the thirty-two brave men, who remembered the fate of Fetterman a few months previous and fought with the fury of desperation, After more than three hours during which repeated attacks were made, the Indians withdrew, leaving hundreds of their dead upon the field.

Powell’s lost was insignificant, (the defenders lost 6 men) and his brave stand had a crushing effect on Red Cloud, and Fort Kearney was ever thereafter allowed to remain unmolested. From the Indians it was later learned that nearly three thousand Indians had participated in the encounter, and that almost a third of that number were killed.

The reinforcements from Fort Phil Kearney arrived before the small force of defenders was overrun, bringing along a mountain howitzer, which ended the battle.

Years later, in 1914, The Oregon Trail Commission was appointed by Gov. Joseph Carey, with the purpose being to place suitable markers along the old Oregon Trail. However, the work hauled during WW1, and resumed in 1919.

From the Laramie Republican on August 2, 1919

The Oregon Trail Commission is taking up work of placing marker at spots of battles. Its first piece of work since the war was to find the location and place a marker on the site of the Wagon Box Fight, which occurred 52 years ago on Aug 2, 1867.

Sergeant Samuel S. Gibson, of Omaha who took part in the Wagon Box fight, has been secured and he will go tomorrow to the scene and locate the exact site of the battle. As soon as he turns in his data, steps will be taken to arrange for having a marker placed at the site, and the Sheridan Commercial club is already planning an impressive program to commemorate the occasion.

Sergeant Gibson will also visit the old Fort Phil Kearney site, from which the men went forth to take part in the historic Wagon Box fight. The location is on the northern boundary of Johnson County, and whether in Johnson or Sheridan county will not be established until Sergeant Gibson reports. The fight is said to have taken place a few miles to the west of Fort Kearney.

And again, on August 8, the Laramie Republican had this.

Gibson designated the exact location of the battle ground. His memory was so vivid and he was so positive in all matters pertaining to the exact location that none disputed his memory.

Another coincidence that corroborated his statement was the fact that he was able, as well as others, to find many shells on the ground that he designated as the location of the wagon boxes. According to the account in the Sheridan Post. Sergeant Gibson pointed out each spot where incidents of the fight occurred.

He showed where the gallant Jenness fell, his heart pierced by a bullet. He pointed out the pluce where the brave Haggerty crouched and though shot through the shoulder continued to fight on. The last attempt to rush the position was made by thousands of Indian on foot who came up the hill from the west in V formation with the chief, a nephew of Red Cloud, at the apex. In place of coming at a run they advanced slowly singing their battle chants, and it gave the soldiers a chance to take careful aim and make every bullet tell.

This was the last general advance and sometime later reinforcements from Fort Phil Kearney appeared and the Indians departed, going north toward the Tongue River. The question was asked Sergeant Gibson how many Indians took part in the battle and how many were killed and wounded but he frankly admitted he did not know. Red Cloud in ‘75 told General Custer that he went into the battle with 3,000 warriors and came out with 1,900 and Mr. Gibson says he can readily believe Red Cloud’s estimate was approximately correct, for when the Indians departed, they had a string of ponies carrying the dead and wounded that was apparently nearly half a mile long.

After re-enforcements arrived, the soldiers were given a shot of whiskey to calm their nerves, and then they returned to the fort. Additional civilian survivors had hidden in a nearby draw and made their way back to the fort after dark.

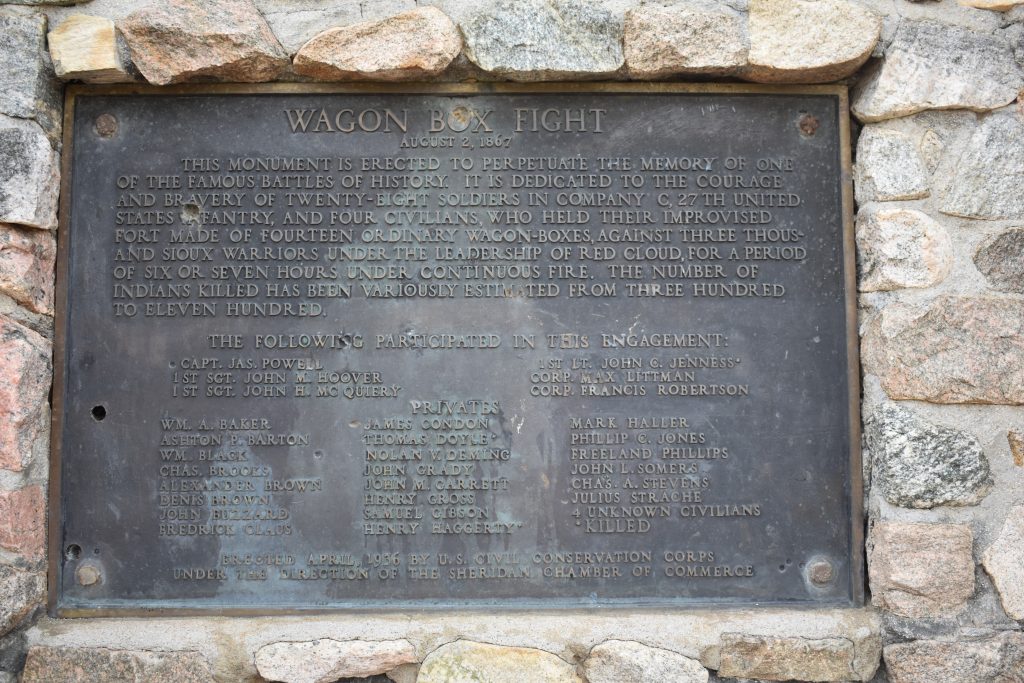

Many years later, a stone monument along with a plaque with the names of the soldiers and civilians involved in the fight was erected in April of 1936 by the Civilian Conservation Corps under the direction of the Sheridan County Chamber of Commerce.

Today, the site is a Wyoming Historical Site, and along with the stone marker are several information signs about the battle, a remembrance of the time when the Native American’s fought to reclaim their home lands from the white invaders.